Key Takeaways

Co-living meets evolving housing needs given long-term population trends, and is an essential component of a well-balanced housing mix.

- It responds to the needs, values and lifestyles of Gen Z and Millennials, offering independent living that is more affordable than the PRS sector.

- It can meet the needs of the growing number of international migrants, who typically rent for their first 5 years of UK residence and may need additional support to navigate and integrate within the UK.

- Co-living can help to professionalise the growing rental sector, picking up some of the slack from the exodus of buy-to-let landlords, instead supplying better quality homes which are designed and built for renters.

There is a high demand for co-living and a large market, with supply currently nowhere near demand.

- The core market size is just under 3 million people, with current supply meeting just 0.3% of demand.

- Most co-living residents can be categorised as young professionals, with a high proportion of residents being from overseas, though occupants vary widely by scheme, and there is potential for co-living to serve a wide variety of people at different life stages.

- People are drawn to co-living for a variety of reasons, including its favourable price and location, the ability to live alone but socialise, and the convenience and flexibility of the contract and pricing model.

Co-living has proven itself to be a financially attractive and sustainable sector, and the co-living market has grown and consolidated rapidly over the past decade.

- Yields in co-living are regarded as attractive, and as such there has been a growing interest from investors in UK co-living, including an increased amount of institutional capital.

- Impact-driven investors have also taken notice of co-living as a sector with attractive returns which also delivers on social and environmental impact.

- The co-living concept has matured and been refined over the past decade, and now has an established professional ecosystem which continues to evolve and improve co-living as a product.

Co-living has several environmentally sustainable features, which make it well-positioned to offer a holistic approach to sustainable housing.

- Co-living offers greater opportunities for retrofit building conversions over other residential typologies, due to its greater flexibility in design and amenity spaces optimising deep floor plates. The all-inclusive rent model also incentivises building owners to invest in energy efficiency to keep their rents competitive.

- Co-living has infrastructures designed for efficiency and sharing, which have positive environmental outcomes, including: centralised and well-connected locations as well as on-site coworking (minimising transport emissions), high density buildings which enable energy efficiency for space heating and cooling, and sharing of amenities and objects which reduces per person embedded emissions.

- Co-living operators are well-positioned to encourage environmentally sustainable behaviours such as energy saving and recycling, and can spread further awareness through sustainability-related events. Evidence shows that residents can also encourage each other to be more sustainable.

The evidence shows that co-living is financially and environmentally sustainable housing that is currently chronically undersupplied in the UK, and provides a much-needed housing solution which can contribute to Government targets to build 1.5 million new homes over the next parliament.

Through specialist events, co-living site visits, conference presentations and press releases, WhyCo aims to promote co-living as a key part of the UK housing industry.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Since circa 2015 co-living has gathered significant momentum around the globe. Traction continues to grow in the UK: last year there were more planning applications and permissions granted than ever before (circa 9000 and 6200, respectively).1

This new iteration on an old way of living is being driven by urbanisation, changing lifestyles, and as a result, evolving housing needs.

Given these long-term trends, co-living is no fad, but an essential component of a well-balanced housing mix, which must be considered as part of the UK Government’s strategy for building 1.5 million homes over the next parliament.

This article explores the macro trends which are driving changing household compositions and housing needs, the demand for co-living, its viability and sustainability as a business model, and finally its potential to be a particularly environmentally sustainable form of housing.

What is co-living?

Co-living is a modern form of professionally managed rental housing which emphasises community, affordability and convenience. Residents have access to private compact studios and communal spaces, which often include shared kitchens, coworking, gyms, and lounge areas.

Rents are inclusive of bills, and tenancy contracts are often more flexible than traditional rental homes. Both residents and the local neighbourhood are encouraged to socialise via events programming and design to encourage social interaction.

Changing Housing Needs for a Changing Population

The population of the UK is changing, both demographically and behaviourally. As such, housing must adapt to meet the new challenges and needs which arise from these long-term changes.

Changing Values, Lifestyles and Households

The population of the UK is changing, both demographically and behaviourally. As such, housing must adapt to meet the new challenges and needs which arise from these long-term changes.

The needs of Gen Z and Millennials – co-living’s main demographics – have been evolving since the post pandemic period, and many value mental health, environmental sustainability and alternative work dynamics and environments.

Gen Zs and Millennials are deeply concerned about environmental sustainability, with around 60% feeling anxious about climate change recently and 64% willing to pay more for eco-friendly products. They also prioritize work/life balance and purpose, increasingly seeking flexible work options like part-time roles and four-day work weeks.

Mental health amongst these demographics remains a challenge — only about half rate theirs as good, with 40% of Gen Zs and 35% of Millennials saying they feel stressed all or most of the time.2

It is well known that UK lifestyles are changing, with people living with parents for longer, buying a home later in life, cohabitation and marriage decreasing, and the average age of marriage and becoming a parent going up.3

Linked to some of these changes is the unaffordability of housing. Median house prices have risen from 3x average household income in England in 1997 to 8.26x average household income in 2023,4 with predictions that house prices will continue to rise.5

As such, private renting has become more common, increasing from 3.1 million households in 2008-09 to 4.7 million households in 2023-24. It now accounts for 18.5% of all households 6 and is the second largest tenure in England.7 Recent rent rises, averaging 8.7% from January 2024 to 2025,8 have also made renting prohibitively expensive, with the average proportion of income spent on private rent being 45%.9

There is also a rise in the number of people living alone, with 42.3% of households being one person no children homes, with an expectation that this will increase by 3.2% over the next 5 years.10

How Co-Living Meets These Changing Housing Needs

- With flexible lease contracts, events focused on personal and professional development and social impact and sustainability-driven initiatives put on by operators, co-living communities respond to many of the needs and values of Gen Z and Millennial demographics.

- Co-living can deliver high quality rental housing which is particularly suited to one person households (and in some cases couples), thus being well-tailored to the UK’s lifestyle shifts.

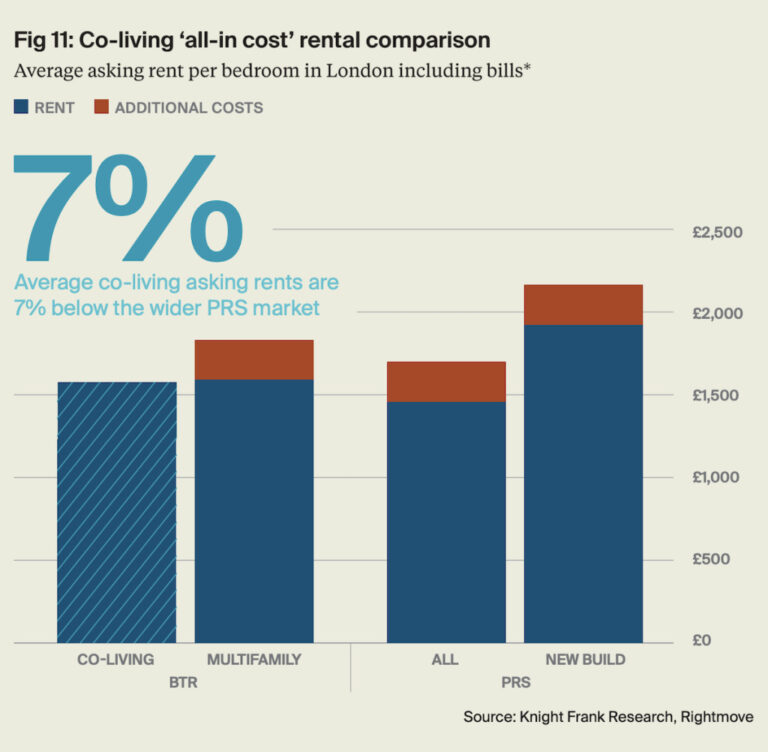

- Co-living enables independent living that is on average 7% more affordable than the PRS sector,11 giving a viable and attractive option for those who would not like to house share, but also do not necessarily want to, or cannot afford to, live alone.

Co-living is sort of like a stepping stone in living alone independently [...] sort of the starting point of living and feeling settled.”

-Amanda, co-living resident

A Growing Population Due to International Migration

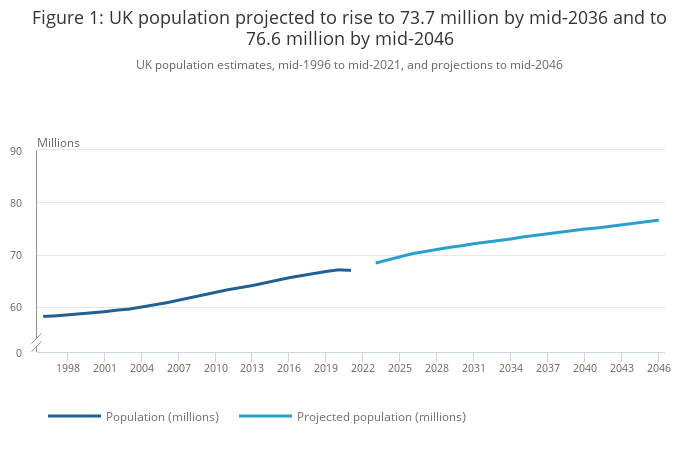

Population growth is estimated to come mainly from international migration.14 The most common reasons that people migrate to the UK is family (44%), closely followed by work or study (43% combined).15

London and the South East have the highest proportion of international migrants,16 though recently this trend has changed, with net migration in London slowing, and increasing rapidly in North West and North East regions. This may be due to London’s high cost of living, in particular housing, which is the least affordable in the UK.17

How Co-Living Meets These Changing Housing Needs

- More housing is and will be needed, at speed and at scale. Based on the UK’s average household size (2.36 people) an extra 550,847 homes over the next five years will be required for the growing population. This is on top of a backlog shortage of 4.3 million homes.18 Co-living can deliver housing at speed and at scale: indeed, the number of co-living schemes submitted for planning has increased year on year, including an 87% increase in 2024 vs. 2023.19

- Co-living can increase housing capacity in urban centres, which are most attractive to migrants due to their economic and cultural opportunities.

- International migrants, especially those who move to the UK for work or study, may also need extra support to navigate and integrate with the UK. Furthermore, as most international migrants are likely to live in rented accommodation for their first 5 years of UK residence,20 greater provision of rental housing is needed to meet current and upcoming demand.

I was searching for a co-living space, because I thought that would be the best way to move to a new country, especially as a new person who's going to work there, that would be an opportunity to network, if needed, but also make friends. [...] It was mostly for the security of it, not just as in security from invaders, whatever, but security mentally as well. Just knowing that I wouldn't be completely alone. I wouldn't be completely thrown into another country and just expected to do everything on my own."

-Dilek, co-living resident

The Private Rental Sector Demand-Supply Imbalance

The PRS sector makes up approximately 18.5% of households (5.3 million households), with estimations that this will grow to 21.2% by 2028 (6.2 million households).21

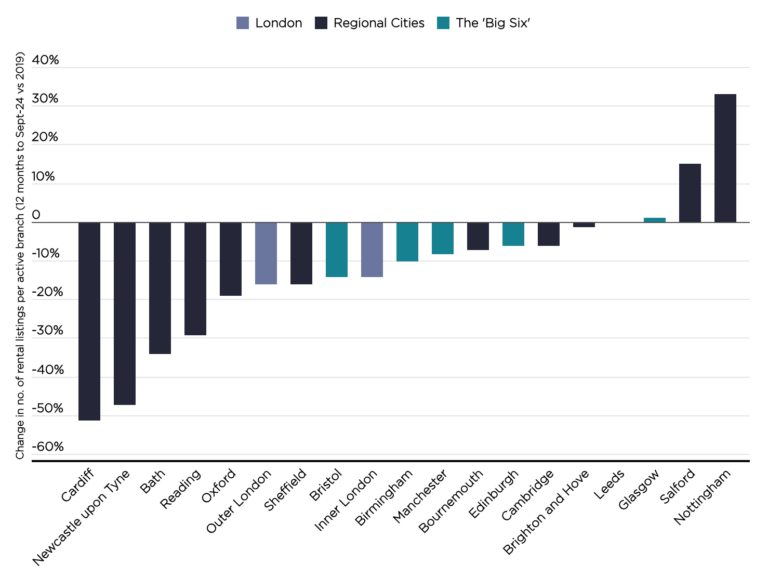

Whilst the demand is rising, supply has fallen significantly, with analysis by Savills showing that the number of rental listings decreased by 15% from 2019 to 2024.22

A recent survey found that 31% of landlords are intending to sell their properties within the next two years.23 Reasons for falling supply are varied, and include tax increases, increased regulation, and high interest rates. In particular, the number of HMOs has fallen, with an 8% decrease when comparing 2018/19 to 2023/24.24

Overcrowding in the PRS sector is also an issue, with 8.5% of PRS properties being overcrowded in England, and 4.3% in Wales (compared with 1.9% of owner-occupied properties in England and 1.2% in Wales).25

How Co-Living Meets These Changing Housing Needs

- The co-living sector is showing strong growth, and as such can provide a valuable supply of high-quality rental housing at speed and at scale.

- Co-living offers an attractive, higher quality, and safer alternative for those who may have otherwise rented HMOs

- Co-living can help to professionalise the growing rental sector, picking up some of the slack from the exodus of buy-to-let landlords, supplying better quality homes which are designed and built for renters.

“[I] literally couldn't find anything. Anytime there was a viewing for anything, there were like 50 people that would sign up [...] it was so difficult. [...] I walked in here [...] and I was like: oh my god, this is gorgeous! [...] it was just such a warm atmosphere. I'd heard “no, no, no, no, no” for so long, all of a sudden it was just like: “yeah, we'll sort you out” [laughs]. It was that easy.”

-Jasmine, co-living resident

The Demand for Co-Living

The long-term lifestyle and population trends explored in the previous section strongly indicate that co-living will have a sustainable role for UK housing. This section specifically explores evidence for co-living demand, and data on the demographic traits of co-living residents.

Core Market and Market Size

The demography of residents tends to vary by scheme, though data from Knight Frank, Newmark and Conscious Coliving indicates that:

- 72% of residents are between 26-40, and of that group, 35% are between 31-35.26

- 46% of residents are from overseas

- Couples represent between 10-35% of occupants

- The average salary of residents is £37,375, though earnings vary widely

- On average, resident tenures last between 9-18 months.27

- Professions vary widely, and include people working in technology, design, marketing, sales and hospitality. Data from one operator found that 17% of employed residents held key worker positions.28

CBRE identifies Experian’s ‘Rental Hubs’ demographic segmentation as a likely target market for co-living, who are summarised as ‘educated young people privately renting in urban neighbourhoods’.29 People who fall into this category make up 8% of the UK population (5,306,184 people).30

CBRE furthermore identifies those privately renting alone or with homesharers, aged 26-45 as a key market, putting the market size at 4.4% of the population (2,947,895 people), or 30% of those who privately rent.31

Kirsten Dyer, Senior Director at CBRE shares that:

Strong demand for co-living has also been identified in large cities with prohibitively high house prices. In particular, London, Edinburgh, Manchester, Bristol, Birmingham, Leeds, Cardiff, Glasgow and Sheffield are identified as key target markets for co-living.32

Having said this, schemes have seen successful delivery and take-up in secondary cities, such as Exeter and Reading, and further schemes are in development in Woking, Bath, Brighton and Sheffield, plus numerous other locations.

For these examples, location is key, with schemes often in proximity to work hubs, for example hospitals and other industries that require housing key workers.

Beyond Core Co-Living Demographics

As a small and relatively nascent sector, understanding of who lives in co-living and why is still growing. Whilst the majority of residents are aged 26-40, anecdotally, there are often a good portion of residents in their 40s, 50s and 60s.

Some co-living operators even report having long-term residents who are families with young children, who appreciate the easy access to events and safety features of the building.

Outside of the UK there are specialist co-living communities aimed at active seniors and intergenerational living (see for example The Embassies and ALFA).

These examples are indicative evidence that co-living can serve a wide variety of people at different life stages.

Why Do People Want to Live in Co-Living Schemes?

People are drawn to co-living schemes for a variety of reasons, including:

- its relative affordability,

- well-connected locations,

- the ability to live “alone” but meet new people and socialise,

- access to events and built-in community,

- the convenience of having bills and amenities included in one price,

- the sense of safety from having a building management team,

- and the high quality of buildings.

For more information on this, see the ‘An attractive option for urban professionals’ and ‘How can co-living enhance social connection and resident wellbeing?’ sections in our previous article in the WhyCo research series, Co-living: A Catalyst for Urban Regeneration.

The Co-Living Value Proposition: A More Affordable, All-Inclusive Bill

A unique selling point of co-living is its relatively affordable and convenient pricing model, in which residents pay one fee which tends to include rent, council tax, bills, wifi, access to amenity spaces such as coworking, gyms and cinema rooms, and access to social events.

One of the biggest deciding factors [...] was the convenience of the pricing model. [...] Relatively, I think it's a fair price because you obviously have the convenience of it all when you get all the facilities. [...] My alternative was to look for a one-bed flat for myself and with a private landlord. Realistically it was going to be difficult to find something in this sort of area that I was looking for, for less than maybe 15 to 1700 a month and that wouldn't include bills, utilities, council tax, ground rent, all that sort of stuff.”

Sam, co-living resident

When looking at the inclusion of bills, co-living schemes are on average more affordable than PRS accommodation by 7% and BTR accommodation by 14%.33

This price differential will be larger when incorporating other included costs, such as gym fees.

Research by Savills found that while overall co-living in London is more affordable than renting a one-bed flat, there are some areas of London, such as Croydon and Harrow, where co-living and one-bed rents are comparable.

Here, those who choose co-living may prefer the location, additional amenities or ability to socialise, over the additional privacy and private space of a one-bed.34

Case study: Folk Palm House

Palm House is a 222 bed co-living scheme, based in Harrow, North London, is owned by DTZ Investors and managed by urbanbubble under the operating platform Folk Co-living. Living at Folk Palm House can save residents around 10-20% compared to a typical studio apartment in the same area.

Included in the bill for a Folk studio is also a fully furnished private studio, onsite café, bar, cinema and roof terrace, 24/7 on-site support team, resident mobile app and zero deposit or admin fees – all of which contributes to the relative affordability of coliving versus typical studios.

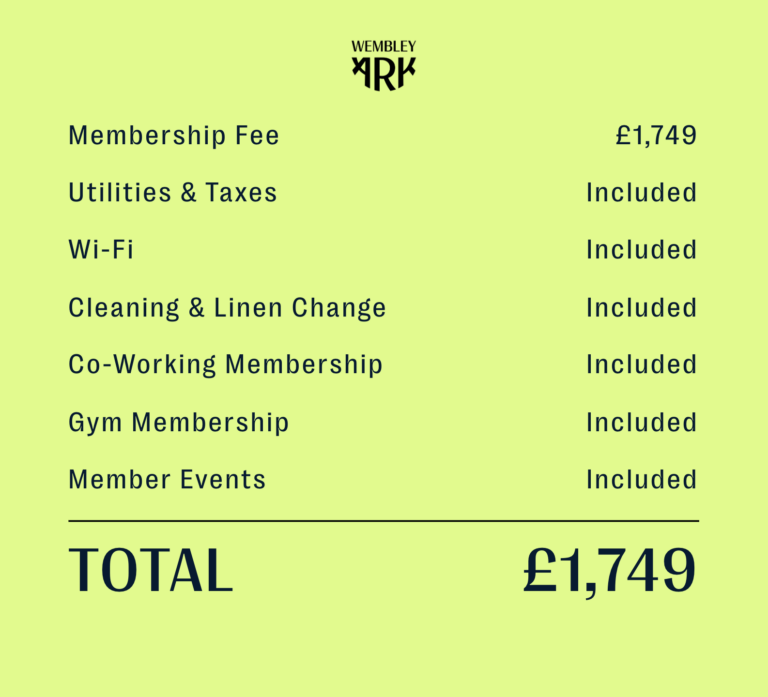

Case study: Ark Wembley

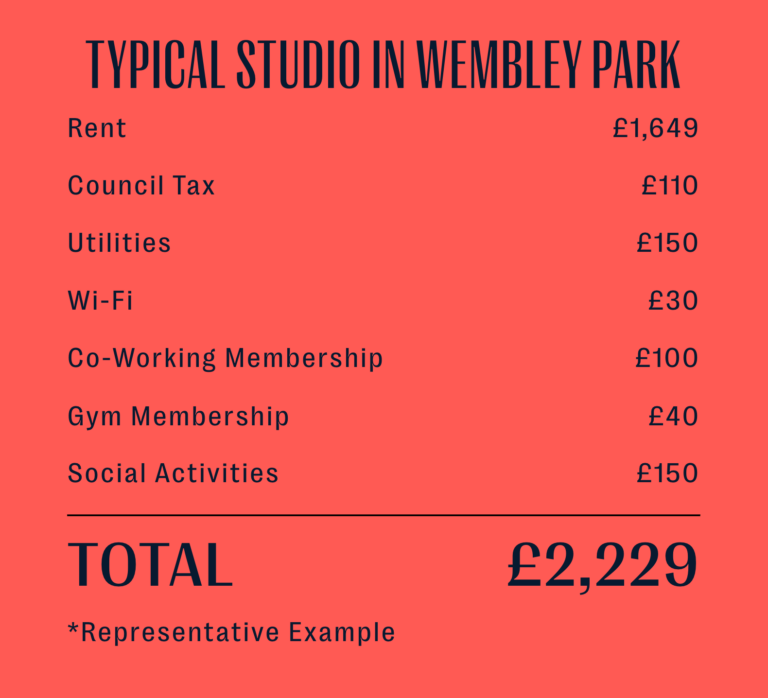

Ark Wembley, based in North London, is a 300-bed co-living scheme, which offers both long- and short-stay accommodation. Ark was created by Re:shape, is co-owned by Re:shape, Generation Estates and Crosstree, and operated by ARK Opco and VervLife. Their studios, with all bills and additional coliving perks included, are nearly 20% cheaper than a typical studio in Wembley Park.

Undersupply and High Demand

As of Q1 2025 there are just under 9,000 operational co-living beds, with circa 14,000 beds across 53 schemes at permission stage, and approximately 17,000 beds across over 60 schemes at the application/pre-planning stage.35 While the sector is growing quickly, it is still nowhere near to meeting the potential demand of circa 3 million (see Core Market & Market Size section above).

High demand has been illustrated by consistently strong lease-up rates in the sector, with schemes often being fully leased within 3-6 months, or even 100% pre-let.36 37

The above evidence indicates that demand for co-living is nowhere near being met by supply, and that this nascent sector is yet to fulfill its potential.

Market Consolidation and Growth

This article has so far argued that there is a strong and under-fulfilled demand for co-living that is supported by long-term trends in changing populations and lifestyles. This section describes and discusses the professional ecosystem which has emerged to contribute to the growing co-living market and its consolidation and growth in the UK.

A Sustained and Growing Interest from Investors

There has been a growing interest from investors in UK co-living, including an increased amount of institutional capital. Yields for co-living are regarded as attractive, and generally sit in between build-to-rent and student accommodation.

A 2023 survey found that 45% of institutional investors who own £75 billion+ of UK living sector assets planned to invest in co-living by 2028, and 32% had already invested.38 Notable investors include DTZI, Bridges Fund Management, Crosstree, Cain International, and Blackrock.

Altogether, since 2020, almost £1 billion has been invested in the UK co-living market, with co-living spending making up a fifth of the total invested in the UK build to rent market in Q1 of 2024.39

According to CBRE analysis, co-living thus far shows similarities to the emergence of the UK PBSA (purpose-built student accommodation) market over a decade before, which had an early concentration of schemes in London, before regional developments became more common.40

The success of the PBSA sector therefore offers some indication of how the co-living sector may develop over time with enabling policy support in place.

Impact-driven investors have also taken notice of co-living as a sector with attractive returns which also delivers on social and environmental impact. Bridges Fund Management, which is currently working with developer HUB on several UK co-living schemes including Yardhouse, Cornerstone and Assemblies, views the potential for co-living to meet net zero goals.

Celia Harrison, Investment Director at Bridges Fund Management, believes that co-living in an important part of providing quality housing in the UK:

Other signs of market consolidation include recent exits and sales of co-living developments, including the Node Brixton sale last year to the University of Cambridge via an account managed by Canadian manager Realstar.

There has also been a rise in mergers and acquisitions in the wider co-living market, for example European operator Habyt’s acquisition of US operator Common, and other brands such as Quarters over the years.

The Growth of the Professional Co-Living Ecosystem

Since the establishment of The Collective’s flagship Old Oak scheme in 2016, the UK’s co-living sector has evolved and diversified. Lessons learned have been translated into ‘Gen 2’ co-living schemes (e.g. Folk Co-living, Ark Co-living, Dandi, Gravity Co-living), which opted for larger private spaces and more centralised shared amenities.

This cohort of industry players have refined and truly proven the concept, as illustrated by their strong occupancy rates and high levels of customer satisfaction (see for example Folk Co-living, which scores 4.69/5 on Homeviews).

The next generation of co-living is showing further, insight-driven evolution, which includes an emphasis on social and environmental sustainability (see Cornerstone, Press Works and Narrowhouse), regional locations, and diversification of unit and amenity type to suit specific audiences.

Now almost a decade later a professional ecosystem for co-living has become established, formed of a mix of start-ups, such as re:shape, Halcyon and Noiascape, and existing companies in related sectors such as build-to-rent and student accommodation who moved into co-living, examples being VervLife, urbanbubble, and HUB.

Co-living developers and operators are supported by a range of sector specialists, from real estate agencies (e.g. CBRE), furniture providers (e.g. The Furniture Practice), to tech providers (e.g. Spaceflow), legal practitioners such as Shoosmiths, and specialist building consultants such as Rund.

The sector’s impact is such that it now has a dedicated policy working group through the real estate industry’s membership body, the British Property Federation.

The appeal of the sector is multi-faceted: its attractive yields, high demand and potential for growth, high occupancy rates, and the appeal of a sector which has strong social and environmental impact potential, all contribute to its desirability.

Damien Sharkey, Managing Director of HUB, a progressive developer with three co-living schemes currently in construction or planning, said:

Altogether, it is clear that there is the investment and professional ecosystem and expertise needed for the sustainability and continued high quality of the sector.

On collaboration with public stakeholders for the growth of co-living in the UK, Michael Howard, Managing Director of urbanbubble – a leading operator which manages three co-living schemes with over 800 co-living beds – said:

Driving Environmental Sustainability

Environmentally sustainable homes are both key for the health of people and planet, and important when avoiding obsolescence and stranded assets, given the evolving regulatory landscape around energy performance of homes and other environmental demands.

Indeed, residential building emissions are the second-highest emitting sector in the UK economy, and the UK’s Climate Change Committee’s 7th Carbon Budget (released March 2025) states that emissions from the residential sector need to fall by 66% by 2040.41

As a sector, co-living tends to have certain inherent advantages in terms of environmental sustainability, relating to construction, infrastructural elements, operational practice, and opportunities for behaviour change amongst residents.

This section explores and discusses these advantages, demonstrating that co-living is well-positioned to offer a holistic approach to sustainable housing.

New Opportunities for Retrofit

Retrofitting existing buildings rather than creating new builds offers significant opportunities for lowering life cycle carbon emissions (provided retrofits are built with sustainable operations in mind),42 with embodied emissions on average being halved compared to new builds if the sub structure, frame, upper floors and roof of the building are kept.43

Whilst more than ever, developers and planners are opting for retrofit over new builds, co-living offers greater opportunities for building conversions than more traditional residential typologies. This is due to co-living having different minimum space standards and greater flexibility for the incorporation of amenities in deep planned buildings often associated with office conversions in design.

Ed Sharland, Associate Director at Assael Architecture, shared his view that co-living tends to have the edge when it comes to retrofit opportunities:

Case Study: HUB's Cornerstone & Assemblies

Located by the world-famous Barbican in the heart of the City of London, Cornerstone is an ex-office space, being transformed into 174 co-living homes, with a ground floor cafe and shared amenities.

This scheme, developed by HUB, in partnership with Bridges Fund Management, meets the demand for more affordable, centrally-located worker accommodation.

In total, 90% of the substructure and 65% of the superstructure will be reused, with an estimated 34% carbon saving when compared with a new build.

The Cornerstone scheme is part of a wider strategy by HUB and Bridges Fund Management to acquire offices that are ‘stranded assets’, retain their structure and improve their thermal performance, delivering a building with low embodied and operational carbon.

Through this strategy, they aim to deliver more affordable homes in well-connected locations, and revitalise city centres in a way that builds on existing heritage and has the support of local communities.

HUB and Bridges Fund Management currently have further retrofit co-living schemes including Assemblies, 150 Minories, a deep office retrofit that will host a cafe and workshops which can be enjoyed by the wider community.

The reuse of the building frame will allow for saving embodied carbon and the building will be operated on all electric after refurbishment. There is also potential for the building to be net zero in its operational phase.

Case Study: The Rex in Kingston

The Rex co-living development, approaching completion as of Q1 2025, is a 212-bed part-retrofit co-living scheme, based in Kingston, London.

Amro Partners has developed what was originally a 1960s office and in 2012 was converted into student accommodation. Embodied carbon reductions of 40% and 50% have been achieved for the substructure and superstructure respectively, and the project is set to exceed operational energy performance requirements by 60%, and achieve a full suite of sustainability ratings, including BREEAM ‘Outstanding’, Fitwel 3* and WiredScore ‘Platinum’.

Paul Belfield, Executive Director of Rund, who are supporting Amro Partners at The Rex as Employer’s Agent, Quantity Surveyor and Clerk of Works (Quality, Fire and M&E), said:

Incentivisation for Energy Efficiency

The rental sector suffers from an energy efficiency paradox. With landlords controlling structural elements of the building, but tenants paying for the energy they use, there is perceived to be little incentive for landlords to invest in energy efficiency, as they will be the ones to pay for it, but ostensibly will not reap the financial benefits.

Regulation has therefore been a key driver of energy efficiency improvements in the rental sector, and whilst changes are being implemented, progress is slow, and regulations are not always complied with.44

Co-living shifts this dynamic. As utility bills are typically included at a flat rate as part of the rent, landlords (e.g. co-living operators) must bear the costs, while also keeping their prices competitive. Therefore, there is a direct incentive for owners to create energy efficient buildings.

Case Study: Narrowhouse in Birmingham

This 249-bed co-living scheme by GNM group has the ambition to be the UK’s tallest energy-positive building, generating more energy than it consumes through high-efficiency, building-integrated solar panels.

The scheme, set in the heart of Birmingham’s canal network and currently in the pre-planning phase, is estimated to save 87.9 tonnes of CO2 annually, feeding excess clean energy into a microgrid, to benefit the local community.

An Infrastructure for Efficiency and Sharing

The unique selling points of co-living often inherently align with environmentally sustainable living.

Co-living is primarily aimed at urban professionals, and as such, well-connected and well-served locations are expected, and indeed specified within the Large-scale purpose-built shared living London Plan Guidance.45

Research by Lichfields has found that in London the majority of schemes fall within areas of high PTAL (public transport accessibility level, a measure used in transport planning to assess the level of access to public transport), and have very limited parking, or are car free, with ample bicycle storage.46

Proximity to city centres has been found to be strongly correlated to more active travel, public transport use and lower carbon footprints.47

Provision of Coworking Spaces

Co-living schemes typically provide on-site coworking, which can be both for residents and for people from the local community.

Research has found that hybrid working, in which people use local co-working spaces in combination with commuting to their office, can reduce carbon emissions by up to 70% through reductions in transport and building-related emissions.48

High Density Living

The typical quantum of co-living schemes which have been granted planning permission is 282 units,49 with an average size unit of 20 sqm, and the average internal communal area of 5.5 sqm per unit, plus an average external communal area of just over 2 sqm per unit.50

This makes co-living highly efficient in terms of density, whilst still creating good quality homes which support resident wellbeing.

With the largest share of UK housing emissions being the energy used to heat spaces, homes in which less energy per person is needed for heating can significantly reduce housing emissions.

One case study of cluster-flat co-living found that carbon emissions arising from space heating were at under a third of an average single-family household.51

The Sharing of Amenities and Objects

Numerous objects and amenities within co-living schemes are shared. For example: washing machines, kitchen appliances, vacuum cleaners, gym equipment, seating, electronics and more.

This sharing reduces duplication of goods amongst residents, thereby reducing embedded carbon emissions (the emissions attached to the raw materials, manufacture, transport and disposal of objects). Embedded emissions are difficult to measure, but make up the largest proportion of carbon emissions.

The sharing (and borrowing) of household goods and items has even been streamlined through technology solutions like Tulu, which provides on-demand access to the day-to-day home essentials that residents want and need.

Co-living offers a rare opportunity in housing to reduce these emissions in a novel and effective way.

Encouraging Sustainable Behaviours

The management companies which run co-living schemes are well-placed to encourage sustainable behaviours and positive relationships with nature from residents.

This not only can have positive outcomes for the environment, but has also been shown to increase self-reported happiness and wellbeing,52 thereby increasing resident satisfaction.

In this section, Folk Co-living is used as a case study to explore different ways in which operators can encourage sustainable behaviours and nature connectedness.

Case Study: Folk Co-living

Folk Co-living, the co-living brand owned by DTZ Investors and managed by urbanbubble, have three co-living schemes in London, with over 800 co-living studios.

Encouraging Energy Efficiency and Recycling

Folk buildings are powered by 100% renewable energy and are highly energy efficient. Air-source heat pumps and solar panels also help improve the building’s energy efficiency.

Residents are encouraged to conserve energy by turning off lights and using electricity responsibly in their studios. While utility bills are included in the rent, a fair usage policy is in place, and each unit is equipped with an electricity meter, allowing for clear communication with residents about their usage and ensuring the policy can be applied effectively.

Additionally, residents are encouraged to recycle as much as possible to minimise their environmental impact.

Folk also manage the collection of unwanted clothes and shoes by residents, and in 2024 donated 2,550KGs of clothes and shoes, resulting in a reduction of 21.52 tonnes of carbon emissions.53

Engaging Residents with Sustainability and Nature Connection

Over 2024, Folk held approximately 30 sustainability-related events, including their regular gardening club, litter picking, and recycling arts and crafts events. These events are run by both the Folk team and Folk residents, who can choose to be Sustainability Ambassadors.

Having residents who are Sustainability Ambassadors fosters engagement and empowerment, and enables a closer connection between the managerial team and the residents. Sustainability Ambassadors are responsible for delivering sustainability initiatives on site as well as supporting the integration of new residents.

Their other responsibilities include championing resident behaviours that are positive for the local community and the environment, and sharing feedback with the team. As such, these ambassadors play an important role in fostering a culture of environmental sustainability, and clearly signal an intent from the operating team to encourage positive behaviours.

Encouraging Biodiversity

At Folk’s The Palm House, a 222-unit co-living scheme in Harrow, North London, Folk has installed herb garden planters on the 8th floor terrace area. These have been originally planted and continuously managed by the Folk residents, and contribute to biodiversity, healthy eating, nature connection and the mental health of residents.

On the same site, Folk has also installed seventeen bird boxes and five bat boxes, supporting the local ecosystem through giving birds and bats safe places to roost.

Resident-to-resident Sustainable Behaviours

Small-scale, qualitative research by Conscious Co-living found that whilst there was little evidence that co-living residents were more environmentally conscious than most, they did engage in certain activities with positive environmental outcomes.

The setting of co-living, in which residents shared communal areas, communicated frequently, and had opportunities to run events, enabled these activities in a unique way.

These findings are aligned with academic research on shared living communities and environmental sustainability, which found that shared living can enable positive environmental behaviour change.54

Residents consistently reported sharing excess groceries and items they knew they would not use, thereby reducing food waste.

If I'm going away [...] I'll just stick [unused food] in the fridge in the communal area. And that's another thing I love, that I don't have to chuck it away. Because I'm not realistically gonna get the train over to a mate's house to give them my onions or something! And I just leave a note saying ‘please use’ [...]”

- Jasmine, UK co-living resident

Similarly, residents would offer possessions they no longer wanted to their co-living neighbours, which could be easily enabled by instant messaging.

In our group chat [...] if someone's leaving and they don't want to bring their stuff, they'll leave it out and say: ‘does anyone want [this]?’”

- Amanda, UK co-living resident

There were also examples given of “positive peer pressure”, whereby residents would remind each other to use resources efficiently.

Someone else from the building that maybe might create a group or create a discussion or message in a group chat saying: ‘oh, you know, guys, just be mindful about using, about how much water you're using.’ [...] People will say those sort of things [...] I feel a lot of people in the building have these sort of values.”

- Amanda, UK co-living resident

Residents who did feel passionate about sustainability had the opportunity to share their passion with others, and help others to engage in pro-environmental activities. One resident described how a co-living neighbour had encouraged her to run a sustainability-related event.

She was incredible... she was a great advocate for sustainability. She'd do, you know, like a gardening club, but also pushed me to do my own event, and we did a fashion sustainability event where even people from the local community came in and swapped clothes.”

- Claire, UK co-living resident

Co-living enables the sharing of resources, knowledge and interests, which – provided there are some residents with environmental values – can allow cultures around sustainability and nature connection to flourish.

Co-Living is Futureproof Housing

Co-living is here to stay, and will become a fixture of the housing landscape for the foreseeable future. As a product it aligns with population and lifestyle trends, and has high levels of demand, and strong interest from investors, developers and operators. Importantly, it also offers many advantages relating to environmental sustainability, as well as social value for both residents and local communities.

For co-living to meet its potential, support is needed from both local and national governments.

The WhyCo campaign, backed by stakeholders across the co-living sector, will continue to produce resources for and work with policymakers to advocate for this new and exciting way of living.

*This article was authored by Conscious Coliving, with CBRE as a key contributor.

Key co-living facts

- What is Co-living? Co-living (or coliving) is a modern form of professionally managed, rental housing which emphasises community, affordability and convenience. Residents have access to private and communal spaces, which often include shared kitchens, coworking, gyms, and lounge areas. Rents are inclusive of bills, and tenancy contracts are often more flexible than traditional rental homes. Both residents and the local neighbourhood are encouraged to socialise via events programming and design to encourage social interaction.

- How many co-living homes are in the UK today? According to the most recent UK statistics from Savills, there are now around 9,000 operational co-living beds, with a further 5,500 more under construction

- Where can co-living be found in the UK? Most co-living is currently in London. Though co-living also exists in major cities such as Manchester, Liverpool, and Aberdeen, and smaller cities, including Exeter, Guildford, and Reading.

- What is the current investment landscape like for UK co-living? Recent research from CBRE shows that Over £1.81bn has been invested into the UK Co-living sector to date, of which 68% has been in London.

- Who typically lives in co-living? A wider range of people live in co-living, though it is most often inhabited by young professionals, with the most popular age category being 30-35.

Why Co-living? Research co-leads

Dr Penny Clark

Director of Research & Sustainability

Conscious Coliving

Penny has a research background. Her PhD, which won a Coliving Award in 2022, explored and measured the environmental impacts of shared living communities, and she has since undertaken research on coliving for policy, industry and academic audiences. Penny has been interviewed about shared living in the BBC and the Guardian, along with having written about shared living in publications including The Developer, Coliving Insights, Conscious Cities, and the book, Urban Communal Living in Britain.

Matt Lesniak

Director of Impact & Innovation

Conscious Coliving

As an entrepreneur, community facilitator and impact strategist, Matt Lesniak works at the cross sections of the community building, impact, placemaking and shared living sectors. Matt has been a driving force behind the coliving sector for years, with a CV that includes The Collective, Co-Liv, and initiatives Coliving Insights and the Coliving Awards. Matt is a strong advocate for impact-driven coliving businesses, which embed environmental and social value throughout their communities.

Footnotes

[1] Savills (2025). Spotlight: UK Co-Living 2025. Available at: https://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/229130/372282-0/spotlight–uk-co-living-2025

[2] Deloitte (2024). 2024 Gen Z and Millennial Survey: Living and working with purpose in a transforming world. Available at: https://www.deloitte.com/global/en/issues/work/content/genz-millennialsurvey.html

[3] Office for National Statistics (2024). Milestones: journeying through modern life. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/articles/milestonesjourneyingthroughmodernlife/2024-04-08

[4] Office for National Statistics (2024). Housing affordability in England and Wales: 2023. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/housing/bulletins/housingaffordabilityinenglandandwales/2023

[5] CBRE (2024) House price forecasts 2024 – 2028 average annual change.

[6] Experian (2023) PRS market share 2023 %.

[7] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2024). English Private Landlord Survey 2024: main report. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-private-landlord-survey-2024-main-report/english-private-landlord-survey-2024-main-report

[8] Office for National Statistics (2025). Private rent and house prices, UK: March 2025. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/bulletins/privaterentandhousepricesuk/latest

[9] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2024). Chapter 2: Housing costs and affordability. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/chapters-for-english-housing-survey-2023-to-2024-headline-findings-on-demographics-and-household-resilience/chapter-2-housing-costs-and-affordability

[10] Experian (2023). One Person: No Children Households 5 year increase %.

[11] Knight Frank (2024). The Co-Living Report. Available at: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/2854/documents/en/co-living-report-2024-11304.pdf

[12] Experian (2023). Population (2029).

[13] Office for National Statistics (2025). National population projections: 2022-based. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationprojections/bulletins/nationalpopulationprojections/2022based

[14] Ibid.

[15] The Migration Observatory (2024). Migrants in the UK: An Overview. Available at: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/migrants-in-the-uk-an-overview/

[16] The Migration Observatory (2025). Where do migrants live in the UK? Available at: https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/where-do-migrants-live-in-the-uk/

[17] Greater London Authority (2025). Recent migration trends in the UK and London. Available at: https://data.london.gov.uk/blog/recent-migration-trends-in-the-uk-and-london/

[18] Understanding Society (2025). Insights: Transforming Housing. Available at: https://www.understandingsociety.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/insights/Insights-2025.pdf

[19] Savills (2025). Spotlight: UK Co-Living 2025. Available at: https://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/229130/372282-0/spotlight–uk-co-living-2025

[20] Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology (2017). Migrants and Housing. Available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/POST-PN-0560/POST-PN-0560.pdf

[21] Experian (2023). PRS market share 2028 %.

[22] Savills (2025). Spotlight: UK Co-Living 2025. Available at: https://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/229130/372282-0/spotlight–uk-co-living-2025

[23] Property118.com (2024). Fewer PRS homes in 2025 as BTL lending set to fall. Available at: https://www.property118.com/fewer-prs-homes-in-2025-as-btl-lending-set-to-fall/

[24] Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (2024). Local Authority Housing Statistics data returns. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistical-data-sets/local-authority-housing-statistics-data-returns-for-2023-to-2024

[25] Office for National Statistics (2023) Overcrowding and under-occupancy by household characteristics, England and Wales: Census 2021. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/housing/articles/overcrowdingandunderoccupancybyhouseholdcharacteristicsenglandandwales/census2021

[26] Knight Frank (2024). The Co-Living Report. Available at: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/2854/documents/en/co-living-report-2024-11304.pdf

[27] Gerald Eve (2024). Emerging Trends in Co-Living. Available at: https://marketing.geraldeve.com/hp/lp94_pWEG_fVBo_bLMSr6A/emerging-trends-in-co-living

[28] Conscious Coliving (2025). Co-living: A Catalyst for Urban Regeneration. Available at: https://www.consciouscoliving.com/co-living-a-catalyst-for-urban-regeneration

[29] Experian (no date). Mosaic Segmentation Groups and Types – Rental Hubs. Available at: https://www.experian.co.uk/business/platforms/mosaic/segmentation-groups#rental-hubs

[30] Experian (2023). Rental Hubs value.

[31] Experian (2023). Privately renting singles + homesharers 26-45.

[32] Savills (2025). Spotlight: UK Co-Living 2025. Available at: https://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/229130/372282-0/spotlight–uk-co-living-2025

[33] Knight Frank (2024). The Co-Living Report. Available at: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/2854/documents/en/co-living-report-2024-11304.pdf

[34] Savills (2025). Spotlight: UK Co-Living 2025. Available at: https://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/229130/372282-0/spotlight–uk-co-living-2025

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Savills (2023). Spotlight: UK Co-living 2023. Available at: https://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/229130/347501-0

[38] Knight Frank (2023). UK Living Sectors Investor Survey. Available at: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/1769/documents/en/uk-living-sectors-investor-survey-2023-10535.pdf

[39] Knight Frank (2024). The Co-Living Report. Available at: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/2854/documents/en/co-living-report-2024-11304.pdf

[40] CBRE (2024). How can Co-living help resolve the housing crisis? The investment case. Available at: https://www.cbre.co.uk/insights/articles/how-can-co-living-help-resolve-the-housing-crisis-the-investment-case

[41] Climate Change Committee (2025). The Seventh Carbon Budget. Available at: https://www.theccc.org.uk/publication/the-seventh-carbon-budget/

[42] Schwartz, Y., Raslan, R., & Mumovic, D. (2018). ‘The life cycle carbon footprint of refurbished and new buildings–A systematic review of case studies’. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 81, 231-241. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2017.07.061

[43] Cheshire, D. and Burton, M. (2020). The carbon and business case for choosing refurbishment over new build. Available at: https://aecom.com/without-limits/article/refurbishment-vs-new-build-the-carbon-and-business-case/

[44] Hope, A. J. and Booth, A. (2014). ‘Attitudes and behaviours of private sector landlords towards the energy efficiency of tenanted homes’. Energy Policy, 75, 369-378. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.09.018

[45] Greater London Authority (2024). Large-scale purpose-built shared living. Available at: https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2024-02/LSPBSL%20LPG%20Feb24.pdf

[46] Lichfields (2024). A New Way to Live: Co-Living in London. Available at: https://lichfields.uk/a-new-way-to-live-co-living-in-london

[47] Rodrigues, G. (2021). How urban planning is key to net zero: evidence from London. Available at: https://www.centreforcities.org/blog/how-urban-planning-is-key-to-net-zero/

[48] International Workplace Group (2023). Landmark report reveals hybrid working can reduce carbon emissions by up to 70%. Available at: https://work.iwgplc.com/MediaCentre/PressRelease/landmark-report-reveals-hybrid-working-can-reduce-carbon-emissions-by-up-to-70

[49] Knight Frank (2024). The Co-Living Report. Available at: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/2854/documents/en/co-living-report-2024-11304.pdf

[50] Lichfields (2024). A New Way to Live: Co-Living in London. Available at: https://lichfields.uk/a-new-way-to-live-co-living-in-london

[51] Clark, P. I. (2021). Practices of shared living: Exploring environmental sustainability in UK cohousing, community living, and coliving (Doctoral dissertation, University of Westminster).

[52] Nisbet, E. K. and Zelenski, J. M. (2013). The NR-6: A new brief measure of nature relatedness. Frontiers in psychology, 4, 813. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00813/full

[53] Macdonald, I. (2022). Are we shopping sustainability? Available at: https://traid.org.uk/are-we-shopping-sustainably/

[54] Clark, P. I. (2021). Practices of shared living: Exploring environmental sustainability in UK cohousing, community living, and coliving (Doctoral dissertation, University of Westminster).