Key Takeaways

Co-living is an in-demand and modern form of housing that can contribute significantly to urban regeneration.

Co-living can also help to deliver social regeneration of local areas:

- Providing spaces, resources and events which are available to the local communities they are located in

- Contributing to affordable housing provision through affordable homes, discount market rent homes, or cash-in-lieu contributions to the local authority

- Attracting urban professionals and key workers who may choose to stay in the area longer term

- Creating good quality local jobs

Co-living can enhance social connection and resident wellbeing, which contributes to healthy and happy neighbourhoods. It does this through:

- Regular events which include engagement with local neighbourhoods, volunteering opportunities, and a range of activities to suit different interests and needs

- Design which facilitates social interaction through inviting and varied communal areas and the creation of natural “collision” points and opportunities for interaction

- The practices of resident-facing staff, including encouraging residents to socialise, and taking time and care to look after resident wellbeing and safety

Co-living has a strong potential to achieve high levels of social impact, and should be a standard component of a healthy housing mix in urban areas.

This article is part of a research campaign called Why Co-living?. Through specialist events, co-living site visits, conference presentations and press releases, Why Co-living? aims to promote the benefits and value of co-living throughout the UK housing industry.

Table of Contents

Introduction

While co-living has undertaken a rapid rise in the UK and globally, there has been little information on how co-living schemes can impact their residents and surrounding neighbourhood. Given the ambitious Government target to build 1.5 million homes over five years, local and national policymakers should be exploring how co-living can help meet these targets, while also creating safe and financially accessible homes for an underserved but growing group – renters – along with resources which can enhance local areas. This article explores the potential for co-living to contribute towards urban regeneration, and have a positive impact on residents and their neighbours.

What is co-living?

Co-living is a modern form of professionally managed, rental housing which emphasises community, affordability and convenience. Residents have access to private compact studios and communal spaces, which often include shared kitchens, coworking, gyms, and lounge areas.

Rents are inclusive of bills, and tenancy contracts are often more flexible than traditional rental homes. Both residents and the local neighbourhood are encouraged to socialise via events programming and design to encourage social interaction.

In the UK and globally

Co-living has been on the rise globally since circa 2015, with locations tending to be cities in which there are issues of housing affordability, and young professionals in need of secure and flexible homes.

According to the most recent UK statistics, there are now around 9,000 operational co-living beds, with a further 5,500 more under construction.1 Most co-living homes are currently in London, though more are emerging across the UK, including major cities such as Manchester, Sheffield and Birmingham, as well as smaller towns and cities including Exeter, Woking, and Bath.

The UK market is dominated by large-scale, purpose-built shared living (LSPBSL), with the average number of units in current completed schemes being 202 (rising to 282 for schemes which have been granted planning permission).2 However, smaller schemes of circa 20-50 units exist, as do, rarely, small rural co-living schemes. This report mainly focuses on LSPBSL models.

The UK currently faces a challenging economic and social environment, with a growing population, shifting demographic and societal trends, and the ongoing challenge of improving physical and social public infrastructures. While these issues are interconnected, and span across many sectors, homes have a significant role to play in improving lives and regenerating localities.

Co-living, as a form of housing with a unique blend of characteristics, has a particular potential to aid in urban regeneration. Through a co-living scheme’s engagement with local communities, charities and businesses, along with its potential to provide discount market rent (DMR) housing, and draw or retain professionals to an area, it can contribute to the formation of mixed and inclusive communities whilst also enhancing a sense of place-based connection.

This section begins by responding to some of the common concerns around co-living and neighbourhood integration, and then explores evidence and case studies which demonstrate the positive social impact co-living can have on residents and neighbourhoods.

The perception: the transient nature of co-living residents will have a negative impact on our area.

Local authorities may look upon ‘transient’ residents as unfavourable because it is perceived that these residents will have low commitment to an area, and therefore contribute little to the building of long-term, resilient communities. Greater transience also may make it difficult for local authorities to allocate resources appropriately, e.g. for schools and healthcare, as understanding who lives in their area becomes more difficult.

It is worth noting that the private rental sector has a higher level of transience than any other type of housing tenure, with young people in particular moving more often (54% of 16 to 24 year olds and 24% of 25 to 34 year olds have lived in their home for under a year).3 Co-living tenures, at an average length of between 9-18 months,4 align closely with these trends.

Transience is therefore not an issue isolated to co-living, but a reality of renting, especially for those under 35.

Compared with most other rental typologies, we argue that co-living is well positioned to engender a sense of community and connectedness to place, through the sector’s practices of holding events which connect residents and local people or initiatives and through the availability of spaces and resources to the local neighbourhood – see, for examples, the sections in this article on ‘Neighbourhood integration‘ and ‘How co-living encourages resident connection and wellbeing‘. The inclusion of C3 affordable or DMR homes, as currently included within 54% of London co-living schemes,5 also contributes to the creation of mixed and inclusive communities.

While residents may come and go, the ‘sense of community’ continues and is held by the operating company and team, who play a continual role in maintaining the vision and impact of the community. The fairly predictable demography of a co-living scheme can also be helpful for local authorities in understanding how local resources should be allocated.

The perception: co-living residents are mainly students.

Resident demography varies by scheme, but available data shows that the majority of co-living residents are older than typical student age, with 72% between 26-40, and of that group, 35% between 31-35.6 Some co-living schemes in fact do not allow students, e.g. Vita Group’s Union in Manchester. Providing high quality and attractive homes for the age 26-40 demographic is key in creating thriving places and people, given this group’s high levels of economic and cultural contributions to society.

Anecdotally, the demography of residents in schemes can vary widely, including older people, and as the sector matures further and data is available from more schemes, a wider age range may be observed. For example, Folk schemes have a small proportion of students, at under 10%, and a proportion of residents in their 40s, 50s and 60s.7 As the sector matures further and data is available from more schemes, these wider age ranges may become more common.

One concern that local authorities and prospective neighbours may have about young people living next door is anti-social behaviour, such as issues with noise. Unlike HMOs and other PRS properties, co-living schemes have a management team which can act as a touchpoint for maintenance of relations between residents and neighbours, helping to resolve any tensions that arise. The high level of in-house amenity provision, as well as opportunities to socialise, means that many gatherings amongst residents are contained within the building itself, where residents are under the care of the management team.

The perception: co-living schemes will cause an area to be overdeveloped.

Co-living is typically high density, with the average scheme in planning consisting of 282 units, as of Q4 2024.8 Impacts on the local area are minimised, however, by the high level of amenity and socialisation opportunities within the building, which, when opened to the public, can be a net gain in terms of cultural and social local area provision.

The impression of high density in co-living when compared to HMOs may also be compounded by the fact that co-living typically provides single occupancy units, therefore meaning unit numbers of schemes are roughly equivalent to the number of residents.9 Whereas, C3 residential schemes have mixed unit sizes, e.g. 3 bedrooms and five residents, which may as a result downplay actual density.

The main demographic of co-living, which is professionals aged 26-40 with no children, typically do not place a great burden on public health services, as they are unlikely to use local hospitals or GP practices often, and do not use local schools or other child-related services. The on-site provision of a coworking space (now seen as a “must-have” for co-living schemes) may also minimise impacts on public transport from commuting.

How coliving communities can contribute to neighbourhood integration

Spaces accessible to the public

Co-living schemes have large communal areas, and it is common for some of these areas to sometimes or always be open to the public. These may include areas which are always publicly accessible while open, such as cafes, restaurants, bars, or coworking spaces; and ‘flex’ spaces which are occasionally made available to the local community, such as wellness and event spaces.

Events and opportunities for social impact

Co-living operators also run a roster of events. While most events are aimed specifically at residents, some are also open to members of the public or the local community. Such events offer opportunities for integration between co-living residents and their neighbours, as well as an opportunity for local people to benefit from events which can promote health, culture, wellbeing, skills, and connecting with others.

The importance of connected neighbourhoods

A 2016 study found that disconnected communities could be costing the UK as much as £32 billion per year through loss of productivity and increased burden on police, health and social services.10

Case study : Folk Co-living

Folk Co-living, managed by DTZ Investors and operated by urbanbubble, have three co-living schemes in London, with just over 800 co-living beds. Folk frequently leverage their spaces and resources for social impact at the neighbourhood level to enhance neighbourhood relations, and fulfil ESG goals for their investors and local authority partners.

In 2024, Folk donated 135KG of food to local foodbanks, and held over 27 events which were open to the local community. These included:

- The Winter Fayre in which local businesses set up stalls in the Folk Sunday Mills event space

- A ‘Toys for Tots’ initiative, in which toys were donated to the local children’s hospital, and/or made available at low cost for people from the local community

- A casino night with all profits donated to a local homeless charity

Each of the three Folk sites has a local community partner which can use Folk event spaces for free.

Folk Community Partners

Harrow Association of Disabled People (HAD) have helped thousands of disabled people across Harrow access information, advice and support, providing high-quality services that focus on delivering disabled people equal opportunities and the right to live independently. At The Palm House site, Folk support HAD through offering free of charge co-working and event space and by supporting local initiatives.

Share Community provides programs and activities to help disabled people live happier, healthier and more independent lives by offering accredited training, personal development courses, befriending services, and social events. At their Sunday Mills site, Folk support Share Community initiatives with event space and fundraising.

Carney’s Community helps young people from Wandsworth and Lambeth who face disadvantages and exclusion by providing a supportive environment for people aged 11-30 to reduce reoffending and antisocial behaviour and to empower them with the skills and confidence they need to succeed. At their Florence Dock site, Folk supports Carney’s Community in multiple ways, providing regular access to communal spaces, including the gym for 1-1 sessions and the co-working space for hot desking. Folk also extends invitations to Carney’s Community for various events, such as the Christmas Day gathering and several others throughout the year.

Throughout 2024, the free use of event space by local community partners had an estimated value of £20,225.

Provision of affordable homes

Co-living can offer affordable homes and contribute to the forming of mixed and inclusive communities.

Research by Lichfields found that 54% of co-living schemes in London provided on-site affordable housing provision (typically around 35% of units), consisting of discount market rent or conventional affordable housing.11

Kiran Ubbi, Director at CBRE Planning says:

The publication of the LSPBSL LPG (Large-Scale Purpose-Built Shared Living London Plan Guidance) marks an important moment for the future of co-living in London’s rental market. At a time when conventional build to sell products face challenges, co-living has the potential to aid delivery of living accommodation across the capital. This includes the role co-living plays in contributing to the supply of affordable housing. The LSPBSL LPG recognises that where feasible, on-site provision of C3 affordable should be considered. Therefore, as well as co-living providing an important type of alternative rental accommodation for the capital, it can also meaningfully contribute to the supply of delivering on-site affordable housing. As we look ahead, it will be interesting to observe whether projects that commit to providing on-site C3 affordable housing, rather than opting for cash-in-lieu solutions, can enjoy a streamlined planning process.

For those co-living schemes which have opted for payment in lieu, the average contribution per bed amounts to £10,000. While each scheme is different, this shows the potential for co-living to support councils in their delivery of affordable housing elsewhere.12

Case study examples

Yardhouse, Wood Lane

This 209-bed co-living scheme, developed by HUB and Bridges Fund Management in

partnership with Women’s Pioneer Housing (WPH), and forward-funded by City Developments Limited (CDL), will also deliver 60 affordable homes for single women, as well as WPH’s new head office. The mission of Women’s Pioneer Housing is to provide homes and services for women to achieve their potential, so this development will have a direct social impact.

ARK Wembley

ARK Wembley is a repositioned 300-bed new build apart-hotel into a design-led co-living residential scheme. ARK Coliving was created by Re:shape and is co-owned by Re:shape, Generation Estates and Crosstree. The platform is operated by a newly formed ARK Opco, alongside VervLife as a third party operator. ARK partners with domestic violence charity the Al-Hasaniya Women’s Centre to offer safe, short-term accommodation to women in need.

Folk Sunday Mills, Earlsfield

At Folk Sunday Mills, which is operated by urbanbubble and managed by DTZ Investors, one third of the 315 units are priced at DMR. The building rents discounted studios to two Ukrainian refugees, five young adults who have left foster care, and has one studio for on-call doctors from nearby St George’s Hospital.

An attractive option for urban professionals

The resident profile of co-living

Resident profiles are varied, and dependent upon the location and appeal of specific schemes. However, some trends can be identified.

- 72% of co-living residents are aged between 26-40, with around half of this group being between ages 31-3513

- The average residents salary is £37,375

- 10-35% of residents are couples

- 46% of residents are from overseas14

An option for key workers?

It is a well-known issue that in London and other major UK cities, key workers, such as healthcare professionals and teachers, are often priced out of the city that needs them.

Data from one co-living operator finds that, of those residents who are employed, 17% occupy key worker positions (as defined by UK Government guidance15). This compares with an area average of 29.8% of employed people occupying key worker roles or industries.16 While not equivalent, this figure does indicate that co-living is a viable option for key workers, and can support them in living centrally in the cities that they support.

Why do people live in co-living?

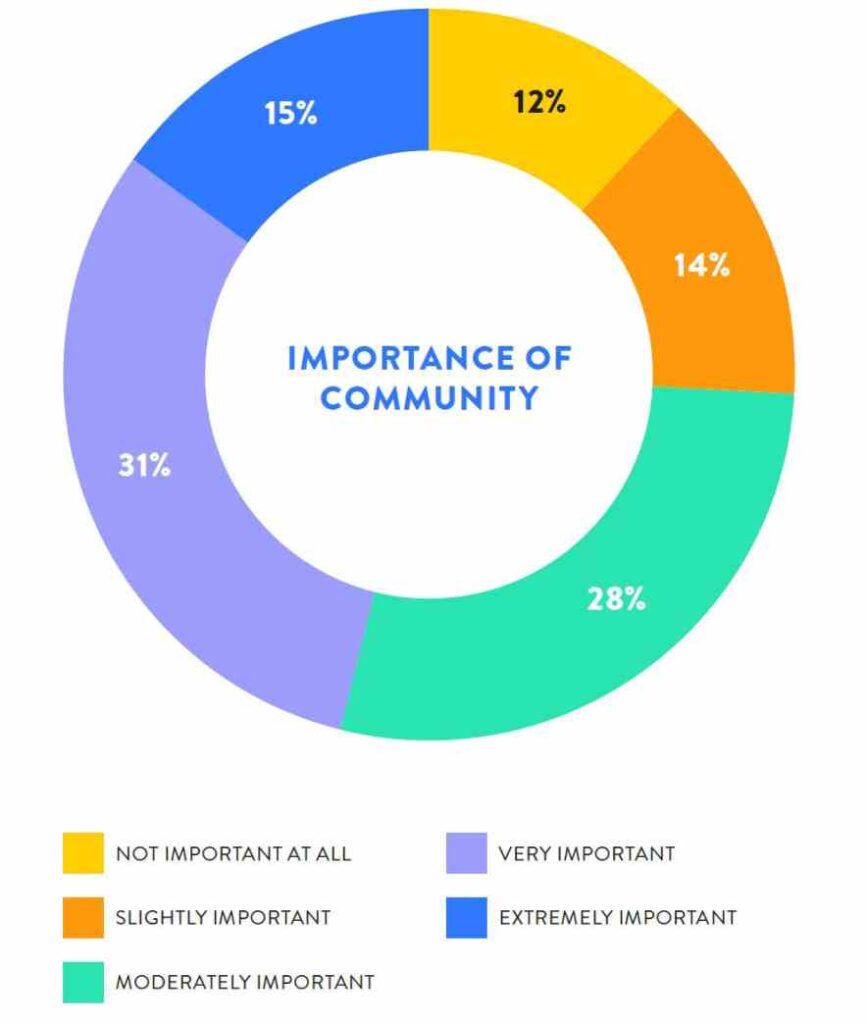

Survey research by Conductor found that the top four reasons that residents give for choosing co-living are: 1. Affordability of rent due to the smaller size of the studio space, 2. Ability to live alone, 3. Desire for a sense of community, and 4. Ability to meet new people.17 These findings show the appeal of co-living being strongly linked with a greater ability for privacy than a house share, but with the option to socialise being important. Indeed, Conductor’s research furthermore found that 74% of residents said that the importance of community in their housing choices is moderately, very, or extremely important.

Resident interviews

Small-scale, qualitative research by Conscious Co-living found that residents’ draw to co-living – unsurprisingly – varied. While the first appeal tended to more often be practical (e.g. the all-in-one bills and overall value, ease of moving, central locations, amenities in the building) over time the role of people and friendships, and ease of socialising, tended to come to the fore as a key benefit.

I think the fact that it's good transport links to where I'm studying, I'm kind of doing six days a week, and so I need Sunday to kind of chill out really… But [...] for example, today I wanted to catch up on some reading, so I came down [to the communal living room] and chilled out and found it very comfortable. [It] just feels like a very comfortable environment.”

- James, UK co-living resident

I was scared of moving to an apartment on my own because I didn't know anyone. I didn't know what was the safe area [and] what wasn't. So I was searching for a co-living space, because I thought that would be the best way to move to a new country, especially as a new person who's going to work there, that would be an opportunity to network, if needed, but also make friends. [...] It was mostly for the security of it, not just as in security from invaders, whatever, but security mentally as well. Just knowing that I wouldn't be completely alone. I wouldn't be completely thrown into another country and just expected to do everything on my own."

- Dilek, UK co-living resident

I think that one thing that made me like the place is the people. I think you become so much more sociable here. You go to events. You make friends. You meet so many people from different parts of the world [...] And I think that's one good thing from co-living, is that you're not always alone [...]”

- Lily, UK co-living resident

I was just really casually looking [...] I walked in here [...] and I was like, oh my god, this is gorgeous! I was like: wow! [...] it was just such a warm atmosphere.”

- Jasmine, UK co-living resident

Can co-living attract residents to an area long term?

Research shows that most residents intend to live in co-living schemes for between 9-12 months, with a considerable contingent also intending to stay for between 12-18 months.18 As far as is known, there has not been large-scale quantitative research on where residents move to after leaving. However, resident interviews by Conscious Co-living found that some had been drawn to the area by the co-living scheme, and now intended to stay longer term. This is tentative evidence that co-living can attract long-term residents to an area.

When I was thinking of: am I going to renew? Am I going to look for somewhere else? I was not looking anywhere beyond [...] or adjacent to [area redacted] [...] because I'm just super happy. I'm happy with the train stations, I'm happy with the buses. I'm happy with how close to London I am, but also not super close to London [...] I would look for somewhere that is [...] definitely in or close to [area redacted].”

- Dilek, UK co-living resident

“I've lived around [area redacted] [in] London all my life and I've never been to [area redacted] before. There was nothing really there for me to live there for, if that makes sense. Like it's a nice area but… If the co-living building was somewhere else then [...] then I probably wouldn't have, even thought of coming [here]. Yeah, but now that I've lived here, I would perhaps settle longer term around here.”

- Sam, UK co-living resident

Case study: local job creation

Businesses can create good quality jobs for those who live locally, which contributes positively to the local economy, can enable people to stay within their local areas, and have a better quality of life through shorter commutes.

Co-living is no exception, and some operators already prioritise hiring local people, such as Folk Co-living, which has 1/3 of their on-site staff based locally.

In interviews, local staff in a UK co-living scheme were asked about the impact of living locally, and what they appreciated about the job.

Honestly, I say this to everyone, but it is my favourite job of all time. Best job in the world in my opinion. [...] my favourite part of the job is the community within co-living. [...] you'll find these people from complete walks of life that would never interact [...] become the best of friends and you'll see them hanging around constantly [...] this job compared to all the others, it's a lot better on the mental health side. So in previous roles, you don't really get too much socialising with other people, you feel sort of only talk to you when they absolutely have to, for example. But here you still maintain that social life while still at work and it doesn't make it feel so much as you're going to work to have to do a job, it's more of you go there to enjoy your time there.”

- Enna, UK co-living staff

“You meet so many people from so many different walks of life and [...] hearing their stories [...] it's quite a learning curve I guess [...] it's helped me even, you know, change as a person as well [...] we've built a great relationship with our residents. [...] It's not like a retail job or an office job, you know, I know in theory these are our customers, but I don't like to see them as customers, you know, like this is their home.”

- Stan, UK co-living staff

How can co-living enhance social connection and resident wellbeing?

In the UK, 45% of adults said they felt occasionally, sometimes or often lonely.19 Those who are particularly at risk of loneliness include younger renters, and those who are single, and live alone.20 Loneliness is strongly correlated with depression and anxiety, which the WHO has ranked as the leading and the sixth cause of disability worldwide, respectively.21 Indeed, research shows that living with more social connection can dramatically lower rates of anxiety, depression and other mental health concerns.22 As well as improving quality of life, this can also save significant costs on health and social care services. For example, one study found that mental health conditions cost the UK economy at least £117.9 billion annually.23

As cities continue to grow and the number of people living alone in developed countries increases,24 housing solutions that incorporate our social needs, particularly for groups of people who are vulnerable to loneliness, are important in helping to create healthy and happy places.

This section explores the evidence that co-living can positively impact resident’s social lives, and then gives best practice examples of how co-living design and operations encourage social connection, a sense of safety, and mental health support.

The evidence for social connection in co-living

Some industry research has evidenced that co-living is enabling residents to connect socially and having a positive impact on loneliness.

Israeli/American co-living operator Venn found that their resident’s loneliness levels dropped by 50% six months after moving in, and that 100% of Venn residents felt socially supported.25

Spanish operator Urban Campus reported that 82% of their residents felt ‘less alone’ thanks to their community,26 and a 2023 report by a consortium of co-living operators found that residents felt closer to their neighbours as a result of co-living.27

Research on loneliness and social connection by Conscious Co-living

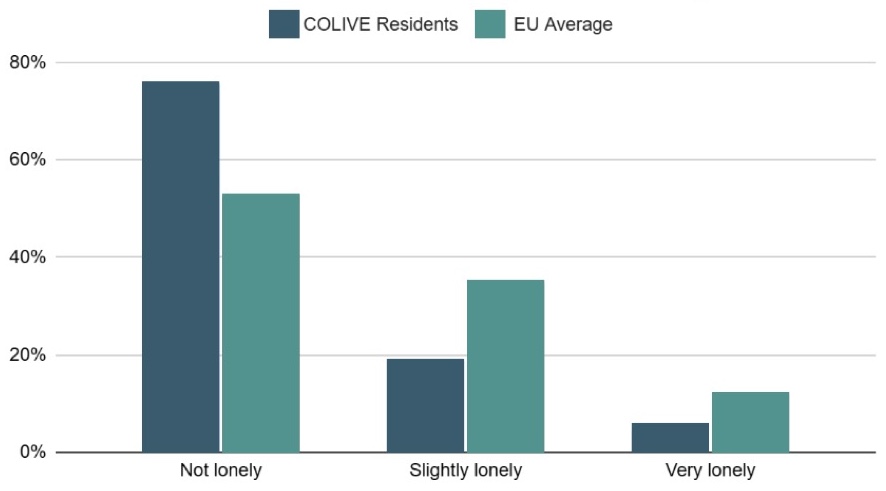

In Q4 2024, Conscious Co-living worked with Swedish operator COLIVE to measure levels of loneliness and social connection in their co-living schemes.

Sweden has an established history of shared housing, including an active co-living sector. COLIVE opened their first site in 2019, and now manage three locations in Stockholm, one in Gothenburg and one in Lund, with 359 beds in total. Residents stay on average between one to two years, with a minimum lease time of two months. The majority of their residents are aged between 20-35, are expats, and single.

A total of 333 residents were invited to take part in a survey about social connection in co-living, with 26% participating in the final survey.

Alongside this survey, Conscious Co-living conducted a small number of qualitative interviews with co-living residents in a UK co-living scheme. Results are presented together where appropriate.

The survey finds that co-living residents have significantly lower levels of loneliness when compared with EU averages.

76% of residents at COLIVE are not lonely (compared with EU average of 53%), 19% are slightly lonely (compared with EU average of 35%), and 5% are very lonely (compared with EU average of 12%).28

70% of residents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “The people at my co-living community play an important role in my social life”. This finding suggests that the lower-than-average levels of loneliness can be connected with the co-living schemes that residents live in (as opposed to friendships that residents have outside of their homes).

Some UK co-living residents shared how the social element of co-living could help to mitigate feelings of loneliness.

I've made many friends now at home, plus I don't have any relatives here, a few close friends but they live quite far… it became some sort of, not a family, but, when you feel lonely, when you feel homesick, you can come down, chill with people, have a nice conversation.”

- Fiona, UK co-living resident

Even if you go in the morning on Saturday for a coffee with someone. Exchange a little bit you know, your mood, if you're lonely or you feel alone, you can go out in the terrace, maybe you can connect with someone, try to open up yourself and this kind of thing.”

- Luca, UK co-living resident

In the big cities, sometimes you feel so lonely, but [...] to find out like a place, that feels like home, and people who feel like your family, it's something very unique, and it's very hard to see right now. And that's one of the good things about living in a co-living, is like this feeling of home, community [...] here you feel that you belong. Every single person belongs to this big community

- Fiona, UK co-living resident

The COLIVE survey found that residents had an average of three friends29 and ten casual acquaintances in their co-living scheme.30 Both types of relationships are important to emotional wellbeing and a sense of belonging.31

Interviewees from the UK all reported having made friends and/or casual acquaintances in their home, with most saying that they had made real and genuine friendships, and a minority, more often newer residents, sharing that they had made acquaintances rather than friends.

The difference it makes even just coming in and just saying hi to a few people [...] I may not go to events that much [...] [but] just that difference of just saying hi to someone and just having a quick catch up, I think I'd really miss that if I went back to just living in just a normal apartment complex"

- Jasmine, UK co-living resident

I've definitely made some real friends here. As with the nature of any of these things, sometimes you know, the relationships are just superficial and just out of convenience. But I have genuinely met some really, really good people [...] and I'll definitely keep in touch with them.”

- Sam, UK co-living resident

At this stage and period of my life [...] I want to hang out, I want to have the social aspect of my life [...] [the] people I've met here, it's like a treasure, especially, in our day and age, when it's hard to meet genuine people, and build genuine connections.”

- Fiona, UK co-living resident

What this building provided for me was access to a social life that's very convenient. I just need to go downstairs to hang out with people I know.”

- Sergei, UK co-living resident

There was also a minority of negative views about the community, that it could be ‘cliquey’, or that only a minority of people were really socially engaged. Indeed, interviews suggested that while some people gained a lot from the social aspect of co-living, others more appreciated factors such as the convenience of the all-in-one leasing model, the on-site amenities, or security of having a front desk.

“Some people have felt that it’s cliquey, and all the rest of it. […] I mean, I don’t socialise enough to make these opinions, but it’s word of mouth.” Claire, UK co-living resident

Interviewees often remarked that they liked the ability to opt in or out of socialising and sharing, with some commenting that, for these reasons, the level of privacy that a studio offered was highly preferable to a house share.

I was new to London and I thought [...] I'd feel more alone living with strangers and having to adapt to their living situation rather than finding my own place [...] I like the fact that I have my own space, but I can still socialise [...] I think is what I enjoy the most, especially being alone in London”

- Claire, UK co-living resident

Some interviewees also commented that they appreciated the variety of people they had been able to meet, which they otherwise would not have been exposed to.

There's so many people from different countries here, [You] get to learn about different cultures, learn about people in different jobs. [...] I'm still in university, but I'm here on the placement year, [and] I've met so many people who do so many interesting things [...] it's just so nice to meet new people outside of university settings where everyone's doing like, the same thing.”

- Lily, UK co-living resident

How does co-living encourage resident connection and wellbeing?

The encouragement of social connections and wellbeing in co-living is intentional, and enabled through regular events, design which facilitates interaction, and the behaviours of co-living staff.

Events

In co-living communities, events are one important means for residents to meet one another. At certain times of year, such as Christmas, those residents who are not visiting friends and family also value events as a way to celebrate and spend time with others.

Due to the flooding the other week, I suddenly am not going home for Christmas. So I was looking at those events, and I was quite pleased to kind of find out about them.”

- James, UK co-living resident

I started going to events a little bit more, and it basically brought me out of that shell that I had of: ‘I don't want to meet anyone’, not because I'm anti-social, but because I was very socially nervous at the time."

- Dilek, UK co-living resident

Case study: Folk Co-living

Folk Co-living, owned by DTZ Investments and operated by urbanbubble, have three co-living schemes in London, with just over 800 co-living beds.

Folk held a total of 286 events across their three sites in 2024, with 70% of those events being related to health and wellbeing. On average, 22% of residents attend at least one event per week.

Examples of health and wellbeing events include a once a week HIIT workout and yoga, wellness sessions involving activities such as journalling and talking about mental health, and includes resident-led events, and a budget to support those.

Case study: ARK Co-living

ARK Coliving was created by Re:shape and is co-owned by Re:shape, Generation Estates and Crosstree. The platform is operated by a newly formed ARK Opco, alongside VervLife as a third party operator. ARK has two sites in London, a 300-bed scheme based in Wembley and a 705-bed scheme in Canary Wharf.

They have a highly varied events program, including game nights, book clubs, exercise classes, cultural celebrations, cookery evenings, litter pick-ups, and more.

Case study: The Gorge

The Gorge, developed by Watkin Jones and operated by This is Fresh, is a 133-bed co-living scheme in Exeter, which opened in 2023. The Gorge runs a Belong Residents Club which includes events such as live music, prosecco parties, afternoon tea, snooker tournaments, cooking demos, and movie nights.

Social contact design

Co-living is typically designed to facilitate social interaction. Communal areas must be inviting, and suitable for a variety of uses and group sizes. “Collision points” enable people to be in proximity with each other naturally, and interactive objects, such as ping pong tables, board games, and chalkboards, encourage people to engage with one another.

Interviewees often reported meeting people within shared spaces.

I like to play pool in the lounge, so I also met quite a few people just playing pool there as well, which is also nice.”

- Sam, UK co-living resident

I was doing laundry, just waiting by the laundry door, I met people, and I chatted with them, and I was carrying something to my home, and someone stopped me, and I'm like, ‘Oh, I wanted that as well’. And we just started chatting about it. And [...] now we are friends.”

- Dilek, UK co-living resident

Case study: Folk Florence Dock

Florence Dock is a 270-bed purpose-built co-living scheme, developed by Halcyon, designed by Assael Architecture, KKA and Atypical Practice, managed by DTZ Investments, and operated by urbanbubble under the brand Folk.

The internal layout of Florence Dock was designed with community-building and social interaction at its core. The site comprises three street frontages with full height glazing, to encourage interactions with passers by. Entrances on two sides allow approaches from different directions.

The ground floor consists of multi-functional spaces which connect the two buildings above, providing shared amenities for residents, the local neighbourhood, organisations and charities. The floor features a reception, coworking space, self-serve bar, library and multiple lounge areas, along with a large commercial space which replaces the commercial use of the previous site.

The role of co-living staff

Research by Conscious Co-living found that resident-facing staff, in particular those who are on-site and frequently engage with residents (e.g. reception staff and event staff) had a key role in both facilitating social interaction and creating a sense of safety and wellbeing amongst residents.

Several interviewees, in particular, women, gained a sense of safety from knowing that there was always staff available to help.

What I love [...] having lived alone for so long... if something happens, there's someone downstairs. [...] that in my mind, is such [a] relief, as a single woman living alone, just it's those little things that just give me a bit of kindness. [...] There is that feeling here that I've never had when I've lived in just normal apartment buildings.”

- Jasmine, UK co-living resident

It's quite safe. You have people to help you most of the time, if you need something you can just pop down…”

- Lily, UK co-living resident

Some staff shared that they engaged in certain practices to help residents stay safe and feel safe. One staff member, Dee, described during a conversation how she would:

Give people her number so that they could call her at night, on the way home from the station, for their safety.

Or that:

If someone didn’t recognise a person in the building they could ask the concierge who could make an enquiry.

Dee’s role extended beyond practical and safety support into emotional support. At various times, she also recounted that she had:

Brought in camomile tea for people who couldn’t sleep; helped people rehearse their work presentations; helped them with job applications; and talked with them for hours during her night shift.

As well as staff’s presence and actions helping residents to feel safe and emotionally supported, they also played a key role in facilitating social connections.

Being able to [...] [make] them feel comfortable within us, it's helping them find their feet sometimes within the community themselves, you know, get them involved in the events and get them involved [...] we have like an ambassador programme here where a resident themselves can be our event hosts on occasions, so it's finding ways to make people more comfortable within themselves as well as within the residents and the community.”

- Stan, UK co-living staff

During interviews, several residents mentioned the important role that staff had played in helping them to develop friendships with other residents:

I didn't really talk to anyone for a long time, and it was actually the staff… They’re all so lovely. [...] Behind the desk, on Sundays it was just a complete riot! Because I got talking to them, and slowly, then I started meeting other residents.”

- Jasmine, UK co-living resident

The staff definitely feel like family and friends as well [...] So all the positive things I said, if they [the staff] weren't positive and good and very nice, I don't think most of them would happen. I don't think events would be happening. I don't think people would be as happy to be there. They're the first people that you meet and talk to, and they're the first people who make you feel at home. So it's thanks to them that this entire space feels like home for me,"

- Dilek, UK co-living resident

Evidence from research by Conscious Co-living shows that resident-facing co-living staff should therefore be seen as a key component of the elements which build social connection and community within co-living, as well as playing an important role in helping residents in feeling safe and supported.

Conclusion

This article has explored how co-living can contribute towards urban regeneration in several ways: through the addition of spaces and resources to local neighbourhoods, provision of affordable and/or DMR housing, local jobs, and through providing quality rental homes for urban professionals, which can contribute positively to residents’ wellbeing via events, design and operations which encourage social connection and other positive behaviours.

Given the continued growth of cities, greater demand and lower supply of rental housing, and rise in people living and feeling alone, co-living presents an ideal solution which should make up a part of the housing mix in any conurbation which wants to attract and retain graduates and professionals, whilst also enriching and regenerating local areas.

Key co-living facts

- What is Co-living? Co-living (or coliving) is a modern form of professionally managed, rental housing which emphasises community, affordability and convenience. Residents have access to private and communal spaces, which often include shared kitchens, coworking, gyms, and lounge areas. Rents are inclusive of bills, and tenancy contracts are often more flexible than traditional rental homes. Both residents and the local neighbourhood are encouraged to socialise via events programming and design to encourage social interaction.

- How many co-living homes are in the UK today? According to the most recent UK statistics from Savills, there are now around 9,000 operational co-living beds, with a further 5,500 more under construction

- Where can co-living be found in the UK? Most co-living is currently in London. Though co-living also exists in major cities such as Manchester, Liverpool, and Aberdeen, and smaller cities, including Exeter, Guildford, and Reading.

- What is the current investment landscape like for UK co-living? Recent research from CBRE shows that Over £1.81bn has been invested into the UK Co-living sector to date, of which 68% has been in London.

- Who typically lives in co-living? A wider range of people live in co-living, though it is most often inhabited by young professionals, with the most popular age category being 30-35.

Why Co-living? Research co-leads

Dr Penny Clark

Director of Research & Sustainability

Conscious Coliving

Penny has a research background. Her PhD, which won a Coliving Award in 2022, explored and measured the environmental impacts of shared living communities, and she has since undertaken research on coliving for policy, industry and academic audiences. Penny has been interviewed about shared living in the BBC and the Guardian, along with having written about shared living in publications including The Developer, Coliving Insights, Conscious Cities, and the book, Urban Communal Living in Britain.

Matt Lesniak

Director of Impact & Innovation

Conscious Coliving

As an entrepreneur, community facilitator and impact strategist, Matt Lesniak works at the cross sections of the community building, impact, placemaking and shared living sectors. Matt has been a driving force behind the coliving sector for years, with a CV that includes The Collective, Co-Liv, and initiatives Coliving Insights and the Coliving Awards. Matt is a strong advocate for impact-driven coliving businesses, which embed environmental and social value throughout their communities.

Footnotes

[1] Savills (2025). Spotlight: UK Co-Living 2025. Available at: https://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/229130/372282-0/spotlight–uk-co-living-2025

[2] Knight Frank (2024). The Co-Living Report. Available at: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/2854/documents/en/co-living-report-2024-11304.pdf

[3] Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities (2023). English Housing Survey 2021 to 2022: private rented sector. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-housing-survey-2021-to-2022-private-rented-sector/english-housing-survey-2021-to-2022-private-rented-sector

[4] Gerald Eve (2024). Emerging Trends in Co-Living. Available at: https://marketing.geraldeve.com/hp/lp94_pWEG_fVBo_bLMSr6A/emerging-trends-in-co-living

[5] Lichfields (2024). A New Way to Live: Co-living in London. Available at: https://lichfields.uk/content/insights/a-new-way-to-live

[6] Knight Frank (2024). The Co-Living Report. Available at: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/2854/documents/en/co-living-report-2024-11304.pdf

[7] Savills (2025). Spotlight: UK Co-Living 2025. Available at: https://www.savills.co.uk/research_articles/229130/372282-0/spotlight–uk-co-living-2025

[8] Knight Frank (2024). The Co-Living Report. Available at: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/2854/documents/en/co-living-report-2024-11304.pdf

[9] Though it should be noted that in co-living, some schemes may also have double occupancy.

[10] Cebr (2017). The cost of disconnected communities. Available at: https://www.safercommunitiesscotland.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Big-Lunch_Cebr-report_Jan2017_FINAL-3-0.pdf

[11] Lichfields (2024). A New Way to Live: Co-living in London. Available at: https://lichfields.uk/content/insights/a-new-way-to-live

[12] Knight Frank (2024). The Co-Living Report. Available at: https://content.knightfrank.com/research/2854/documents/en/co-living-report-2024-11304.pdf

[13] Ibid.

[14] Gerald Eve (2024). Emerging Trends in Co-Living. Available at: https://marketing.geraldeve.com/hp/lp94_pWEG_fVBo_bLMSr6A/emerging-trends-in-co-living

[15] Department for Education (2022). Guidance: Children of critical workers and vulnerable children who can access schools or educational settings. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/coronavirus-covid-19-maintaining-educational-provision/guidance-for-schools-colleges-and-local-authorities-on-maintaining-educational-provision

[16] Data obtained from: Office for National Statistics (2020). Coronavirus and key workers in the UK. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/earningsandworkinghours/articles/coronavirusandkeyworkersintheuk/2020-05-15#how-many-key-workers-are-in-your-area-

[17] Conductor (2024). Rental Series: Co-living. Available at: https://conductor.london/cms-data/thoughts/Co-living%20Rental%20Series-January%202024_4.pdf

[18] Gerald Eve (2024). Emerging Trends in Co-Living. Available at: https://marketing.geraldeve.com/hp/lp94_pWEG_fVBo_bLMSr6A/emerging-trends-in-co-living

[19] Campaign to end Loneliness (no date). The Facts on Loneliness. Available at: https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/the-facts-on-loneliness/

[20] Office for National Statistics (2017). Loneliness – What characteristics and circumstances are associated with feeling lonely? Available at: https://tinyurl.com/mr38u2zz

[21] Mental Health Foundation (2022). Loneliness and Mental Health Report – UK. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/our-work/research/loneliness-and-mental-health-report-uk

[22] Seppala, E. (2014). Connectedness & Health: The Science of Social Connection. Available at: http://ccare.stanford.edu/uncategorized/connectedness-health-the-science-of-social-connection-infographic/

[23] McDaid, D. and Park, A. (2022). The economic case for investing in the prevention of mental health conditions in the UK. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/MHF-Investing-in-Prevention-Full-Report.pdf

[24] Our World in Data (2019). The rise of living alone: how one-person households are becoming increasingly common around the world. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/living-alone

[25] Venn (2019). Semi-annual Impact Report. Available at: drive.google.com/file/d/1Z_sDHoIYoJBqvo4s2Jbo7TFiG-1sSJNA/view?usp=sharing

[26] Urban Campus (2024). Co-living Impact Report. Available at: https://urbancampus.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Impact-Report_EN-2024-1.pdf

[27] Worldwide Co-living Membership (2023). Flexible Living Trend Report 2023 Vol. 1. Available at: www.epsd.co.kr/en/wcm/

[28] Source: EU Loneliness Survey. Available at: https://joint-research-centre.ec.europa.eu/scientific-activities-z/survey-methods-and-analysis-centre-smac/loneliness/eu-loneliness-survey_en Note that loneliness levels are measured using the UCLA 3 Item Loneliness Scale.

[29] A friend was defined as someone you can count on, who brings positivity to your life, and with whom you share a cooperative bond, as defined by leading friendship researcher Lydia Denworth.

[30] A casual acquaintance was defined as someone who you know a little bit, and can have friendly conversation, though your relationship does not have depth or emotional intimacy, as defined by leading friendship researcher Lydia Denworth.

[31] See, for examples: Holt-Lunstad, J. (2017). Friendship and health. The psychology of friendship, 233-248; and Sandstrom G.M., Dunn E.W. Social Interactions and Well-Being: The Surprising Power of Weak Ties. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2014 Jul;40(7):910-922. doi: 10.1177/0146167214529799.

How can co-living help with the social regeneration of local areas?