Co-founder and Head of Sustainability & Research at Conscious Coliving, Penny Clark, has been researching coliving, cohousing and environmental sustainability as part of her doctoral research at the University of Westminster. In this article she shares her initial findings of what makes a community come together to align behind certain values and actions that lead to a more sustainable shared living alternative. This article was originally published in Coliving Insights No.3, ‘Impact & Sustainability in Coliving’.

We have a decade left

to avert irreversible damage from climate changeUnited Nations, March 2019

We know this, yet changing the way we live seems frustratingly simple in abstract, but inscrutably difficult in practice. We are in need of hopeful visions for the future that we can move towards, which are not only physically different, but are underpinned by a different ethos on what constitutes a successful and meaningful life.

Perhaps one of these hopeful visions is community living, in its myriad of forms. It was with this thought that I undertook my doctoral research, exploring environmental sustainability within UK-based cohousing and coliving communities.

My research is looking at both how community living offers physical infrastructures which lower environmental impacts; and, how it might act as a means through which pro-environmental practices and values are spread.

In this article, I will share some of my research findings, along with some prompting thoughts to help you think about how these ideas can be related to a coliving space.

The Research

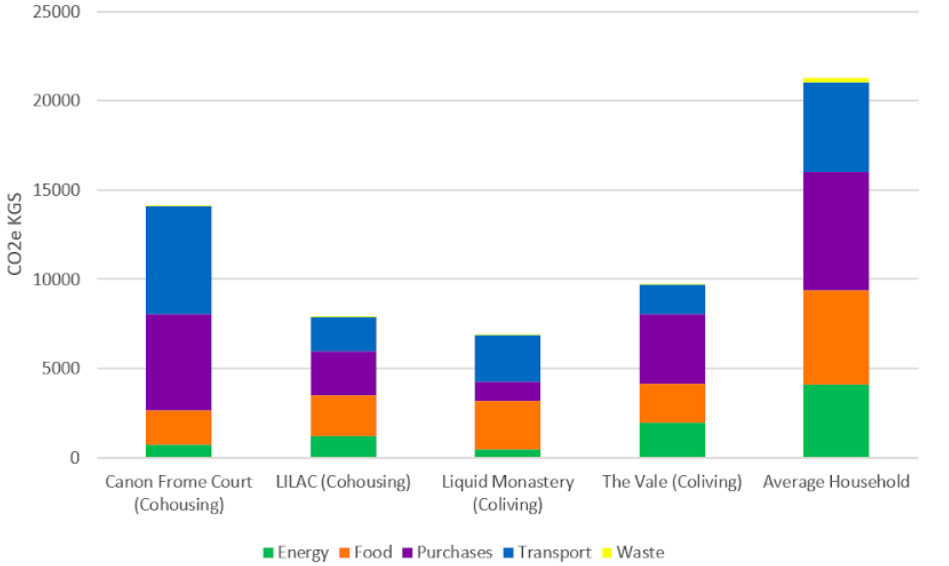

The findings in this article are based on in-depth research with two cohousing and two coliving communities in the UK. Their environmental impacts were measured through surveys and existing records, which have then been converted into CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent – a measurement used to compare the emissions of various greenhouse gases with CO2, based upon their global warming potential) using UK government approved multipliers (DEFRA 2017, 2019).

A figure for the average UK household has been constructed for comparison using secondary data. The communities were also kind enough to welcome me into their homes, so that I could conduct qualitative ethnographic research to try to understand the practices which lay behind the quantitative data.

All participating communities are self-managed and “bottom-up”.

The two cohousing communities, called Canon Frome Court and LILAC, are home to approximately twenty households (around fifty people) each.

The two coliving communities, Liquid Monastery and The Vale, are home to seven and six people respectively. LILAC, Liquid Monastery and The Vale are situated in cities, whereas Canon Frome Court has a rural location.

The Research Results

N=Canon Frome Court Cohousing 6/20 households, LILAC 9/20 households, Liquid Monastery 4/7 residents, The Vale 6/6 residents

[1] Emissions from each community have been normalised to represent a household of 2.4 people, for comparability with an average household.

[2] Please note that The Vale’s ‘Purchases’ data was unavailable. An estimate has been made, obtained through calculating the mean average of purchases data from the other communities plus that of the average household. It is highly likely that The Vale’s actual emissions from purchases is lower than predicted by the graph.

Figure 1 shows that both cohousing and coliving communities emit significantly lower CO2e emissions than the average household. Liquid Monastery’s emissions were at 32 percent of the average household, followed by LILAC at 37 percent, The Vale at 45 percent, and Canon Frome Court at 66 percent.

Enabling Infrastructures in Coliving and Cohousing

In part, these results can be attributed to enabling infrastructures. The two cohousing communities, Canon Frome Court and LILAC, had sustainable materials including solar panels, a biomass boiler, triple glazing and MVHR (mechanical ventilation with heat recovery).

The density of the two coliving communities, Liquid Monastery and The Vale, meant that despite a lack of insulation or renewables, their space heating and electricity usage per person was highly efficient.

The urban location of three out of the four communities also meant that sustainable transport infrastructures were readily available for residents to use, and all communities had room to safely store bicycles.

All communities shared amenities to some extent, which considering the CO2e emissions that occur along the supply chains of all that we buy – from sofas to hairdryers to the kitchen sink – can lead to significant CO2e savings.

Within cohousing communities, sharing tended to be limited to launderettes, outdoor space, workspace and communal kitchens and social areas.

The coliving communities shared almost everything – living space, kitchens and bathrooms. As one resident of The Vale pointed out: ‘we have one TV, and there’s six of us […] if we all had our own flats […] the average person would have a TV [each]’.

This sharing of spaces and amenities shows that environmental sustainability is, to some extent, embedded into the infrastructures of community living. Another thing we can learn from communities such as LILAC, which had fantastic cycling facilities, is that if you want people to engage in pro-environmental practice, make it as easy as possible for them to do so.

This can sometimes require lateral thinking: LILAC did not just offer secure bike sheds, they also had spare parts and tools, as well as residents who provided exemplars of cycling practice, were happy to give advice on cycling routes and to help with bike maintenance.

This last point – that residents encouraged each other to cycle – was of key interest to my research. One question that I wanted to explore was: in these communities, did residents encourage each other to adopt pro-environmental practices?

Creating a Culture of Sustainable Practice

The answer to the above is a resounding yes! They did so often and in many ways. Some examples of this include encouraging each other to use sustainable transport methods, shared meals being vegan, reuse of greywater, and practices of borrowing and mending rather than buying.

Though, as with all social realities, the stories here are complex. When engaging in practices, pro-environmental or otherwise, residents were often having to negotiate social expectations and norms, their own values-systems and habits, as well as what the objects around them enabled them to do.

Whilst by their own admission, residents were not paragons of pro-environmental perfection (after all, who is?), their shared culture fostered raised levels of pro-environmental practice which would have been difficult to achieve without the support of like-minded peers.

But how does such a shared culture occur? In the rest of this article, I describe three key elements which enable a sense of community and pro-environmental culture to be formed within any shared living space.

Shared Values Around Shared Living

It may not be a surprise that most of the residents within the communities I worked with cared about the environment. For a community to engage in a plethora of pro-environmental practices, a certain critical mass of those who care certainly helps.

However, I would argue that for pro-environmental practices to be spread amongst a community, the desire that community members have to share their lives is as important as their desire to live sustainably. Let me give you an example.

One of the coliving communities I worked with ate dinner together each day. To be inclusive to all residents, all meals were vegan or vegetarian. Therefore, residents who would otherwise have been omnivorous became vegan/vegetarian during their dinners.

The desire to share lives with each other often meant sharing practices, and in communities where pro-environmentalism was the norm, this could mean that residents – as one interviewee put it – ‘leveled each other up’ when it came to pro-environmental practice.

Similarly, one of the other wonderful things about community living is the wealth of knowledge and interests that are pooled. This holds true in regards to environmental sustainability, as there are so many ways to care for our environment.

Some people get enthusiastic about draft-proofing for energy efficiency, some know how to fix a bike, some can cook a vegan feast, and some like to plant flowers for the bees… in a community, ideas, knowledge and practices are spread, and the benefits of labour are shared.

To create a culture of environmental sustainability, finding people who value sharing their lives with one another is just as important as finding people with pro-environmental values.

Shared Expectations

A result of sharing your lives is that you have to agree on what bits to share, and how that sharing works.

A common source of conflict is when different community members have very different ideas on how to live together, which – more often than not – stem from underlying different values.

Sometimes these differences can surface long after communities have formed, much to the surprise and dismay of residents.

This is why it is advisable to articulate and be aligned upon expectations – and this is true of environment-related expectations too.

These expectations may take the form of a list of rules, a broader statement on house culture, or a handful of values which housemates discuss and relate to practices together.

Once expectations are aligned, housemates know what they can and cannot ask of each other. In my research, it became apparent that communities which hadn’t articulated and agreed upon expectations around environmental sustainability had a much harder time engaging in sustainability-related projects and practices.

Once you have it in place that pro-environmentalism is embedded within the DNA of your community, it is much easier to suggest hosting sustainability-related talks, or spending some of the budget on draft-proofing.

Articulate and create shared expectations around environmental sustainability. Make it part of the DNA of your community.

Shared Presence

Ahrentzen (1996) identifies shared presence (spending time in the physical presence of one another) as being an essential part of forming a collaborative culture within a neighbourhood, and indeed, this was a finding shared by my research into coliving and cohousing.

Community living enables what is usually private domestic practice to become, to some extent, public. Cooking, washing clothes, gardening, cleaning, reading (and the list goes on) are often carried out in communal spaces.

The visibility of these practices created opportunities for innovation and adoption amongst residents. They could share tips, for example, on growing vegetables or fixing bikes. They might borrow a book they see their housemate reading, and then afterwards discuss its ideas.

The sharing of domestic life also acted to spread and consolidate social norms (pro-environmental or otherwise), which regulate social existence, coordinate resident’s activities, and enhance or maintain the identity of the group (Brown, 2000).

For example, anti-flight attitudes were prevalent in the communities that I studied, not because of a directly articulated culture or rules, but because shared presence strengthened pro-environmental social norms, plus made holidaying habits (and their environmental implications) far more visible.

Shared presence is also a foundational block of forming social cohesion (Festinger et al., 1950). Simply put: those that spend time together are more likely to become friends. During my research I witnessed the importance of these social ties in initiating transitions, whether pro-environmental or not.

One interviewee mentioned that when she suggested implementing new health and safety protocols within the community, everyone in theory was on board with the idea, but it was her friends who showed up to the meeting about it.

This same principle applies to when a resident organises a group gardening session, suggests having a shared meal or launches an initiative to keep chickens! Shared presence, and the social cohesion this engenders, greases the wheels of shared practice.

Shared presence can be encouraged through architectural and interior design principles, such as having shared amenities, shared pathways, gradual rather than abrupt transitions from private to public space (e.g. buffer zones) and opportunities for surveillance (Williams, 2005).

Design of social experience is also key: from creating/curating a variety of events to draw different configurations of residents together, to curating for residents who have similar routines.

Encourage shared presence through spatial design and community experience. This can help to nurture/consolidate an existing culture of pro-environmental practice.

Conclusion

My research has found that coliving and cohousing can have a catalysing effect on pro-environmental practices.

The considerations and negotiations that shared living entails encourages the articulation of values, the desire to share and align on practices, and therefore possibilities for novel pro-environmental practices to crystallise into social norms.

As has been mentioned, social realities are complex, every shared living community is different, and it would be reductive and inaccurate to say that shared living = sustainability.

Yet, with the right conditions in place, there is every chance that a culture of pro-environmental practice can grow. Coliving operators have the exciting opportunity to lay the foundations for a pro-environmental culture, which, if it takes off, will gather a momentum of its own.

It is through such small acts, one by one, here and there, that we create a hopeful vision for the future, embodied in the practices of today.

Thank you to the four communities who not only took part in this research, but opened their doors and made me feel welcome.

This article was originally published in Coliving Insights No.3, ‘Impact & Sustainability in Coliving’.

This article has been authored for you by:

Penny is Director of Research & Sustainability at Conscious Coliving. She has an MSc in Social Research Methods, and her PhD explores how shared living may enable lowered environmental impacts. She has consulted on numerous shared living projects, specialising in impact strategy, concept, and community. Penny has presented at conferences including the Co-Liv Summit, the Urban Living Festival, BTR360 and more. She has also authored publications in The Developer, Coliving Insights Magazine, the book Urban Communal Living in Britain, as well as being interviewed by the BBC and the Guardian about shared living.